Design History: Art Deco

I am surrounded by Art Deco architecture in Cleveland Park, my current neighborhood in D.C., but it isn’t enough. I need to live inside Art Deco, so I signed a lease to live in a 94-year-old building two miles south in the Kalorama neighborhood. I was supposed to move this past Friday, but the catch of near-century-old buildings is that sometimes they fall apart. A loose floorboard resulted in a failed inspection, so, until that’s solved, I am marooned in my 2002 beige box of a condo watching the 1974 Great Gatsby just to feel something.

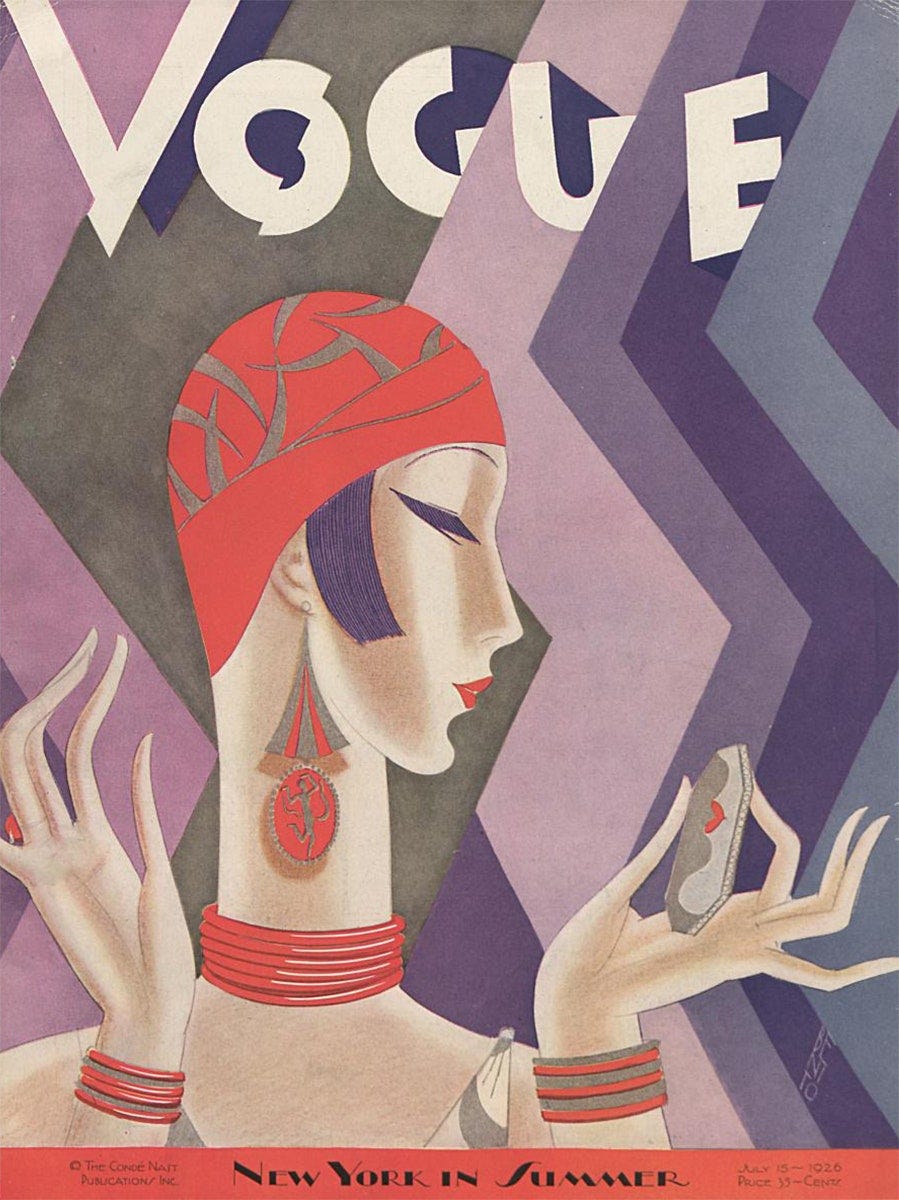

The 2013 Baz Luhrmann Great Gatsby is certainly the most recent and ubiquitous cultural touchpoint of the design style. The movie is a pastiche of black and gold geometry, but it does a decent job representing the floral femininity and vivid colors that defined early Deco on the heels of the softer, nature-oriented Art Nouveau period. This feels like a sharp contrast to an even more well-known Art Deco paragon, the Chrysler Building, with its strident angles and arches. But Art Deco isn’t so much of a singular style as it is a spirit, a collection of motifs that are indicative of a period of time when those who survived—or profited off of—the first world war wanted to live in as of high style as they could afford after years of hardship. The industrial revolution and changing social mores also influenced the style, which aggrandized the power of man and machines.

Art Deco is short for arts décoratifs, which was taken from the title of a 1925 Parisian exhibition of modern decorative and industrial arts. The style was at its peak between the two world wars. There are two other terms worth learning to really get at the heart of the movement: Cubism and Fauvism. Cubism is an avant-garde art movement in which objects are dissembled and reimagined in abstract form to be observed from multiple viewpoints. Faceting, geometric forms, and machinery are all visual themes of the style. Fauvism, the style for which Matisse is best known, used bold, pure color instead of realistic representation. The word comes from the French phrase for “wild beast” because of the characteristic wild, dense brushstrokes. Bring the geometric construction of Cubism and the boldness of Fauvism and you’ve got the beginnings of the Art Deco movement in the early 1900s.

At the turn of the century, the decorative arts were just beginning to be seen as a practical industry of their own, apart from visual art. Think Tiffany lamps—art in use. These products used the finest materials like ivory, ebony, silk, and gold. The development of reinforced concrete allowed for the proliferation of Art Deco buildings. In 1925, Art Deco split into two schools of thought, those who defined the ornate craftsmanship of the initial style, and the modernists who though that the style needed to be made more accessible, and could be for the first time thanks to mass-production and plastic.

As the Great Depression set in in 1929 and styles became more subdued, a toned-down version called Streamline Moderne developed, inspired more by the long lines and rounded edges of ocean liners and by the scientific frontier than skyscraper homages to industrial achievement.

I couldn’t possibly include all of the influences and influencers of Art Deco in this one newsletter. If this has piqued your interest, I hope that you’ll fall down a vivid, angular, romantic rabbit hole of your own.

Let me know what you find.

Until next week,

Elizabeth

This newsletter is just one facet of Zhuzh, my platform dedicated to conscious consumption and making space for delight. I offer secondhand-and-vintage-based wardrobe and interior styling services, art curation, and super chill life coaching. Keep up with me on Instagram and learn more at www.zhuzhlife.com.